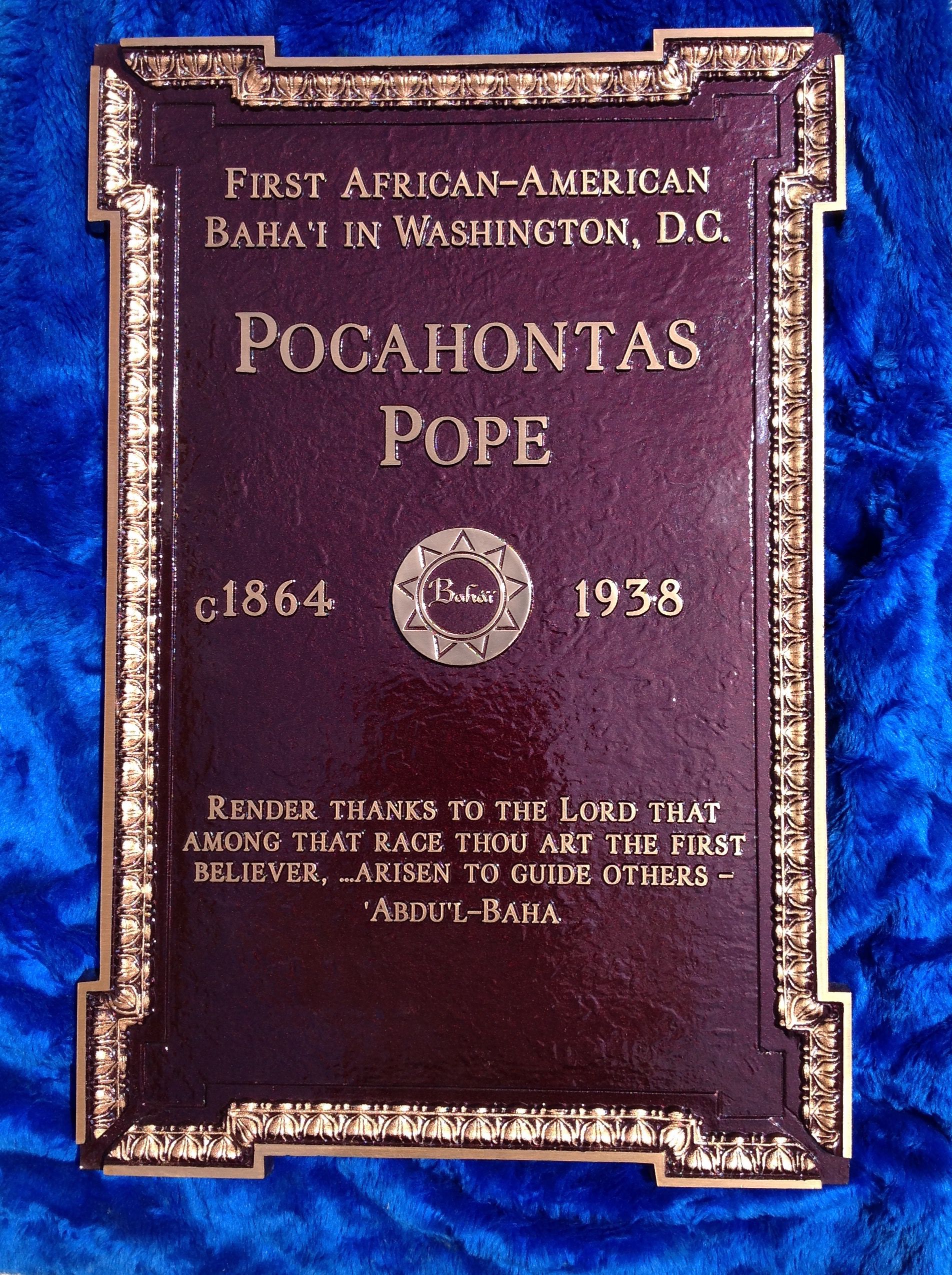

I was in the neighborhood the other day and noticed a for sale sign up at Pocahontas Pope’s old house.

It is going for $899,000, and apparently there was a price drop of $50K. It is a 2 bedroom 2.5 bath home just a few feet shy of 1,500 sq. ft. It obviously has been renovated since 2004, and 2011 and very well. Hopefully, whoever buys it will appreciate the history of that property, even if the structure has been gutted and renovated.

Below I have the old post from 2021 about Mrs. Pope.

With a name like Pocahontas, I’ve been dying to delve into whatever the heck this is, even if it is a dead end.

According to the 1920 census African American widowed dressmaker Pocahontas Pope lived at 1500 1st St NW with several lodgers. Taking in lodgers, the way people take on roommates, was a way to add to one’s income. At first her name did not show up when I did a search of land records. Usually, I search by square and lot number. When I did that her name did not appear and I thought I might have hit a dead end. But then I decided to search by name, and lo, four records appeared, two of them related to 1500 1st St. NW. The other two (docs 192212140170 & 192212140171) was for a LeDroit property, unknown square, lot 3, and it looked like Ms. Pope was acting as a go between.

At first her name did not show up when I did a search of land records. Usually, I search by square and lot number. When I did that her name did not appear and I thought I might have hit a dead end. But then I decided to search by name, and lo, four records appeared, two of them related to 1500 1st St. NW. The other two (docs 192212140170 & 192212140171) was for a LeDroit property, unknown square, lot 3, and it looked like Ms. Pope was acting as a go between.

The records for 1500 1st St were from 1939 and 1940 and Mrs. Pope was already deceased. In the April 1939 trust, devisees of Mrs. Pope’s will, Lawrence A/L Lyles and Clementine K. Plummer borrowed $511.15 from individuals. in 1940, Lawrence A. Lyles, aka Lawrence L. Lyles, sold/transferred the property to co-owner Clementine Kay Plummer. She immediately (same day) borrowed $2,500 from the Enterprise Building Association. Clementine K. Plummer has popped up here and there.

Well what of Pocahontas? Well one of the first records I find about her is her late husband’s will. It’s not much of a will, it basically reads that he, John W. Pope, leaves everything to his wife Pocahontas. What is interesting is where the will was filed, Cape May, NJ. I’m not an expert but there is a link between Cape May and well off DC African Americans. Secondly, who witnessed the will is a who’s who of Black Truxton Circle. The first witness was E. Ortho Peters of 100 P St NW. The second, Dr. Arthur B. McKinney of 63 P St NW. There is a 3rd witness, looks like J.R. Wilder of 218 I St NW.

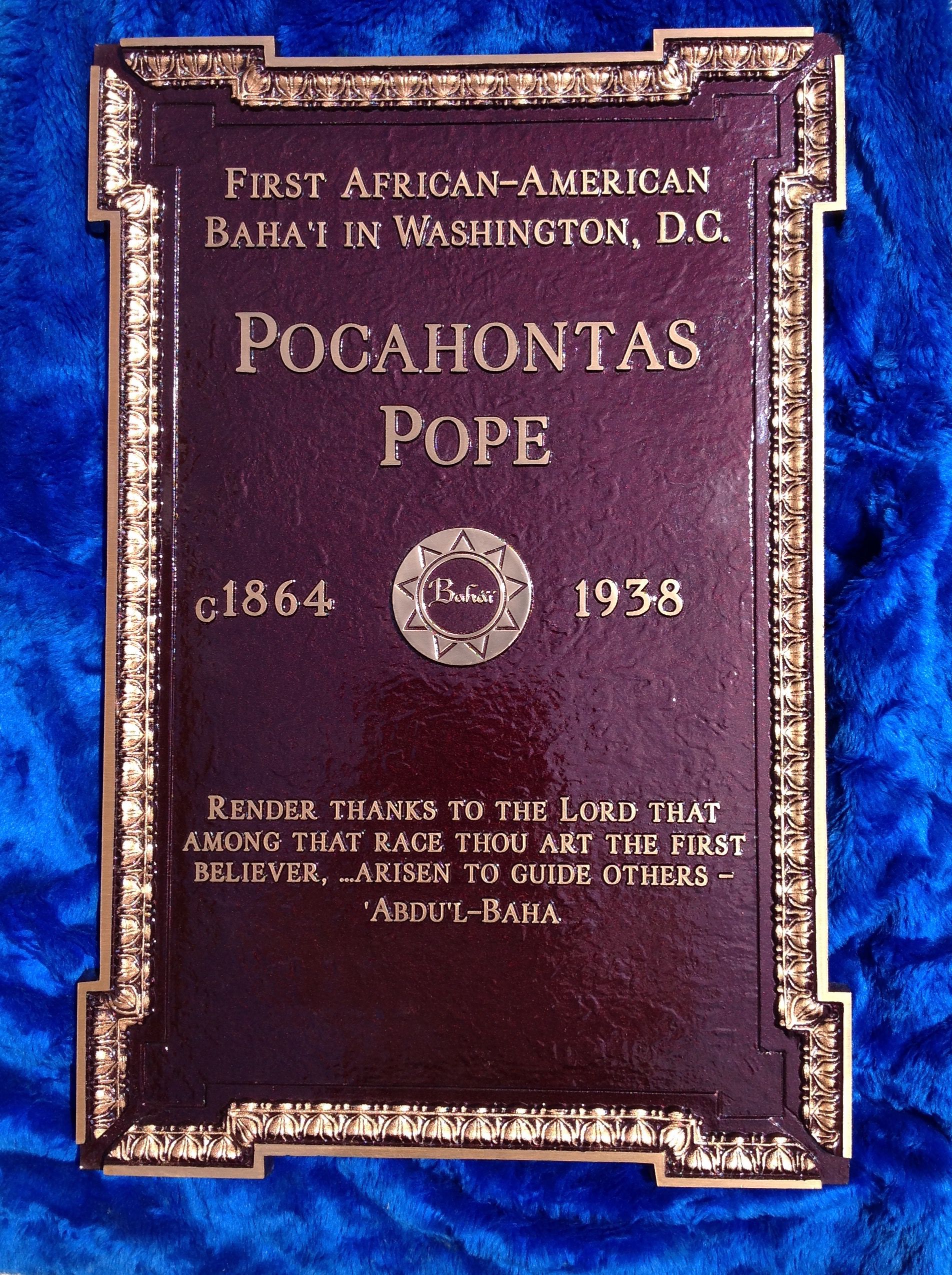

This got me to thinking. Then I did a Googly search on our gal Pocahontas… jackpot. She was an influential member of the Baha’i faith. I’m just going to quote bahaipedia.org for Pocahontas Kay Grizzard Pope’s (~1864-1938) biography:

Her mother Mary Sanlin Kay Grizzard held property including the old County Clerk of Court Office building when it became a private home. Her father John W. Kay is little known but may be the Haliwa-Saponi connection. Soon Pocahontas Kay Grizzard married Rev. John W. Pope, kin to Dr. Manassa Pope, a prominent African-American doctor of North Carolina. John was 8 years her senior and together for some 15 years they served in one or another black schools in Plymouth, Scotland Neck, or Rich Square, NC, areas of deeply rural community. However with the hostility and political changes peaking in 1898 the Popes moved to Washington D.C. where John got a job working for the US Census. Soon both were active in black society, associated with then Congress Representative George H. White and others, giving scholarly presentations, and community activism.

Pocahontas and John never had children and he died in 1918. Pope lived on two more decades without being mentioned in newspapers save when she died – and her last two years were hospitalized. Her house has been noted in tours offered by the Washington D. C. Bahá’í community.

It has? Okay.

The 1920[95] and 1930[96] census’ noted Pope listed with lodgers in the home and working as a dressmaker. The last two years of her life she was a patient at Saint Elizabeth’s hospital.[18] Pocahontas Pope died 11 Nov 1938,[97] late in the evening of cardiovascular failure by hypostatic pneumonia confirmed by an autopsy.[98] She was listed as a Baptist, but in her connection with the Faith in those early years Bahá’ís were not required to leave their former religious communities and indeed sometimes were encouraged to remain active in them.[62]pp. 190, 228-9, 397[99]

One newspaper article notes family relations and other details[100] – nieces Clementine Kay Plummer and Mrs. Charles Hawkins of Portsmouth, VA, nephew Lawrence A. Lyles of Asheville, NC, and that she was buried in the Columbian Harmony Cemetery at 9th Street NE and Rhode Island Avenue NE in Washington, DC after services at the Second Baptist Church on 3rd St. Clementine Kay Plummer was the executrix of her Will.[8] It lists some of the next of kin as inheritors. In order as listed they were: Alex Kay, Ines Kay, Viola Hawkins, Gloria Kay, Andrew Kay, Constance Kay, Cleo Blakely, John W. Kay Jr, June Kay with custodian Mrs. Willie Otey Kay, and Antonio Orsot custodian for Beatrice L. Orsot.

In 1960, the graves at Columbian Harmony Cemetery, including that of Pocahontas Pope, were relocated to the National Harmony Memorial Park in Maryland. [101]

Well that clears up some things and will save me some time when I take a look at Clementine K. Plummer again.