Happy Easter. I’m doing my annual staying home on Easter ritual.

I thought of creating a post called “McMillan was an A-hole, Save McMillan Park!” Something that would address the problem of “Presentism” and McMillan Parkand throw in a little history. Thing was I confused my McMillans.

McMillan #2

By US Government Printing Office – Congressional Pictorial Directory, 89th US Congress, p. 131, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29009100

I was thinking of John L. McMillian, Democrat Representative from South Carolina who ruled the House Committee for the District of Columbia from 1945 until DC got Home Rule and he was defeated. I could go into detail, but for the District of Columbia, African-American citizens and Home Rule, he was an asshole. Google “John L McMillian” and racist, or segregationist.

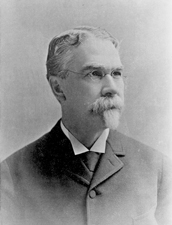

McMillian #1

By Unknown – http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=M000567, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1486060

Republican Senator James McMillan is the McMillan the McMillan Park, or the McMillan Sand Filtration Site is named for and he’s an okay guy, so far. He had a positive impact on the District of Columbia (he’s the McMillan of the McMillan Plan) focusing on the Monumental Core, that area around the Mall and the Tidal Basin. His focus was more on beauty and parks.

So Save McMillan Park

I vaguely remember then ANC and BACA President Jim Berry convincing me to attend as a representative of BACA meetings about developing the McMillan area between 1st and North Cap. It must have been in the early 00s as I can’t find the emails and I really didn’t want to go to those meetings, so I probably deleted those emails. I favor less development in that area than more and it is a shame that what is proposed seems a little over developed, not leaving enough of the the unique qualities of the site. It doesn’t seem to matter that the reservoir and the sand filtration site are on the National Register of Historic Places. Well with enough lawyers and money….. Anyway if you want to fight the proposed development see Friends of McMillan Park.

UPDATE- Earlier I misspelled McMillan. I found that email from Jim Berry asking me to replace him on the McMillan Advisory Group. It was from 2009, not that long ago. My memory isn’t as great as it used to be.

This page contains a single entry by Mari published on March 27, 2016 10:57 AM.