Oh my. I forgot I wrote this last year. Since I have no interest reinventing wheels, here’s chapter 1.

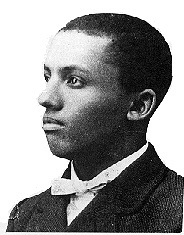

Carter G. Woodson, a Shaw resident, living and working on the 1500 block of 9th St NW, created Negro History Week. This later became Black History Month. Last year I reviewed Carter G. Woodson’s Mis-Education of the Negro. I thought I would review his other book The History of the Negro Church this year.

I’ve read the first chapter. I want to find who edited this thing and do bad things to their grave. If Dr. Woodson edited it, then, this is evidence that authors should get someone else to edit their work.

I’m going to start with something from the book’s preface:

Whether or not the author has done this task well is a question which the public must decide. This work does not represent what he desired to make it. Many facts of the past could not be obtained for the reason that several denominations have failed to keep records and facts known to persons now active in the church could not be collected because of indifference or the failure to understand the motives of the author. Not a few church officers and ministers, however, gladly cooperated with the author in giving and seeking information concerning their denominations.

Given the current lack of popularity, compared to Mis-Education, I will say he had not done his work well. It is a hard read.

My summation of chapter one is that Blacks were a second thought to European missionaries. When they did get around to bringing Christianity to those of African descent into the New World there was a resistance because of an unwritten law (no citations) that once slaves became Christian, they would need to be freed. Catholics didn’t try hard enough and Protestants were more successful at evangelization to Blacks in America.

The one thing I learned reading this chapter was that Quakers taught African American slaves to read in Virginia and North Carolina.

I just wish there were citations for this piece of information and that gets to my first pet peeve. This book is 100 years old and historians of this period have a bad habit of not providing citations to back up anything they wrote. In the copy I have, I do not see end notes, nor is there a bibliography at the end. I blame the time period.

The other pet peeve I’ve revealed early on, was the need for an editor. This was not written for a general audience. It has the charm of a graduate dissertation. He uses $4 words when a $.25 word would do. He’s overly wordy as if he’s getting paid, per word, like a Raymond Chandler novel. The deep need for an editor, someone to strike out some sentences and suggest a better way of making a point, just annoyed the heck out of me.

I just discovered there is an audio book of The History of the Negro Church from December 2020. I will try to listen to this and maybe I’ll do more than 2 chapters this month.

2023 Update- Looking at my notes it appears that he was annoyed that the early Spanish and French missionaries in America were not focused on Blacks. For the Spanish, that’s a no brainer because they exploited the existing population for labor and didn’t need to import Africans, except in some spots. And France had what is now Haiti, and that place ate people up in the machinery of sugar production. People didn’t live long enough.

This chapter covers the late 1600s to about 1764. Geographically it wanders into Latin and South America and the Caribbean.

I was going to sit on this but the FBI’s eFOIA system got some crazy bug and sent me about 18 emails in the past 3 days. I have another non-Shaw related request (I’m curious about stuff) and was hoping it was about that. But nope. It took me a while but I discovered it was the same stuff I got before. It’s just one crazy duplicate email after another. And the FBI gives you 48 hours to click on the link if you want your document. I clicked the link and I got an error.

I was going to sit on this but the FBI’s eFOIA system got some crazy bug and sent me about 18 emails in the past 3 days. I have another non-Shaw related request (I’m curious about stuff) and was hoping it was about that. But nope. It took me a while but I discovered it was the same stuff I got before. It’s just one crazy duplicate email after another. And the FBI gives you 48 hours to click on the link if you want your document. I clicked the link and I got an error.