I’m looking into my collection of photographs and going down memory lane.

I took these photos eighteen years ago. The snow just fell and it was pretty. Pretty until you have to go to work and it gets packed into ice on the sidewalk.

I’m looking into my collection of photographs and going down memory lane.

I took these photos eighteen years ago. The snow just fell and it was pretty. Pretty until you have to go to work and it gets packed into ice on the sidewalk.

This year for Black History Month we’ll review chapter by chapter Alison Stewart’s First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School. This is more Truxton Circle related then this blog’s previous annual looks at Shaw resident and founder of Negro History Week (later Black history month) Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s Mis-Education of the Negro. As Dunbar High School is located in Truxton Circle currently taking up all of Square 554.

Like the last chapter we’re still in the 19th century and not in Truxton Circle.

This chapter covers African American education in Washington, DC in the late 1800s. The president of the Board of Trustees of Colored Schools of Washington and Georgetown in Washington, D.C. was William Syphax. He along with others managed to grow the number of schools for Black students in the District of Columbia from one to 75 by 1872. The board had the support of Senator Charles Sumner, for whom the Charles Sumner School and Museum is named.

Syphax, other Black elites, and other supporters, established in 1870 the Preparatory High School for Colored Youth at the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church. As the school grew it moved around a bit before settling at 128 M Street NW to become the M Street High School, where the Perry School sits, sort of across the street from Truxton Circle. It operated as a college prep high school from 1982 to about 1916 when it moved into Truxton Circle.

There’s a fair amount of politicking mentioned in this chapter. It doesn’t relate to Truxton Circle, so I’m skipping that part.

This year for Black History Month we’ll review chapter by chapter Alison Stewart’s First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School. This is more Truxton Circle related then this blog’s previous annual looks at Shaw resident and founder of Negro History Week (later Black history month) Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s Mis-Education of the Negro. As Dunbar High School is located in Truxton Circle currently taking up all of Square 554.

Okay I’ll make this quick. This starts in the mid 19th century and is about Myrtilla Miner, founder of the Normal School for Colored Girls, then after her death, called the Institution for the Education of Colored Youth, then the Miner Normal School, then the Miner Teacher College.

Since this has nothing to do with Truxton Circle, I’m skipping this chapter.

In this series of looking at the odd numbered side of the 1700 block of New Jersey Ave NW from 1920 to 1930, I decided to look at the other end of the block. The change from 1920 to 1930 for most of the block was from white renters to black home owners. However, in the case of 1741 New Jersey Ave NW, which no longer exists as a house, but part of the parking of a corner gas station, there was no Black resident recorded for the 1930 census.

But then again, the 1930 census had some house number errors, so maybe there was someone there.

First we’ll look at the white renters who lived at 1741 NJ Ave NW in 1920. Look back to 1910, see where they were or learn more about them. Then where they were in 1930. The reason why they vacated is simple, their homes were sold to M. Harvey Chiswell, who then sold the row of homes to African American buyers. They didn’t have much of a choice in the matter.

In the 1920 census, the recorded tenants were the Sussan family. It was headed by a 41 year old baker Charles Sussan, and his wife Lillian. They lived with their three children Charles Jr. (18 yo) (1901-1968); Emily (16); Frank (7)(1912-1987) and Charles’ sister Elizabeth (58 y.o.). Ten years prior the family was living at 612 L St with Charles Sr. working as a baker and Lillian as a dressmaker. They lived with their sons and Lillian’s mother Willey Burgess (1858-1933).

After they left New Jersey Ave the family had moved to Arlington, VA by the 1930 census. Charles Sr. had remained a baker, and lived in the home he owned with his wife and their two sons. Daughter Emily Elizabeth had married and was living with her in-laws at 3110 Connecticut Ave NW. That year Emily would give birth to daughter Hazel Louise Macwilliams (later Brown).

From previous work, we discovered the row of homes on the 1700 odd numbered block of NJ Ave NW were purchased, repaired for sale to African American home owners in Fall and Winter of 1920. 1741 New Jersey Ave NW doesn’t exist, but we can find lot # 30 on a Baist map from the time period.

The first document is a 1923 trust (loan doc) between Mr. and Mrs. James I.(1872–1952) and Lulu (nee Phifer) McCalister and trustees Jesse H. Mitchell and William H. Cowan for $151.89. A November 1923 release document between the Mitchells and W. Wallace Chiswell and Harry A. Kite points to a September 30, 1920 loan. M. (Mary) Harvey Chiswell and W. Wallace Chiswell were part of the operation to sell specifically to African Americans.

1923 was a very busy year as it was also the year James and Samuel McCalister sold 1741 to James M. Woodward, who a few months later sold it to A. Lynn McDowell. In 1925, A. Lynn McDowell, his wife Elizabeth C. and a Julian N. McDowell sold the house to John G. Walker. A little less than a month later Walker sold the property to Mary Hummel. Sometime between 1928 and 1932 the ownership changed to where Conners & Fosters Inc took control of it.

So who were these people? The McCalisters were an African American couple who in 1924 lived at 1509 5th St NW. Prior to that for the 1920 census they were renting 345 Elm St NW. I think that was in LeDroit Park. Mr. McCalister was recorded as a laborer working for the Government Printing Office. I was able to confirm his federal employment by searching the 1919 Official Register of the United States (p.811) to find he was paid 35 cents an hour. In 1930 the McCalisters lived separately. Lulu lived at 946 T St NW, supporting herself as a chiropractor. James was not located for that year. But for 1940 he was a resident at the US Soldier’s Home and Lulu can’t be found. They were back together for the 1950 census living on H St with a lodger. James died in 1952 and is buried at Arlington Cemetery.

This year for Black History Month we’ll review chapter by chapter Alison Stewart’s First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School. This is more Truxton Circle related then this blog’s previous annual looks at Shaw resident and founder of Negro History Week (later Black history month) Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s Mis-Education of the Negro. As Dunbar High School is located in Truxton Circle currently taking up all of Square 554.

The Introduction hinted at the Dunbar High School (DHS) band, chapter one goes into more detail.

It starts in 2004 when music educator Rodney Chambers discovered DHS didn’t have a band director and managed to get a paid job at the school. From there he discovered all sorts of problems that most inner city Black schools experienced. DHS’ grand past had little relationship to its present. Despite that, he managed to grow and improve the band program.

The path to the 2009 Obama inauguration was long. DHS was one of over a thousand applications. Chambers did not advertise that he’d applied for the chance for his band to march. On the day of the parade there were problems. Some kids went missing.

At this point I will take a break from the book to remember the day before. The band was practicing all over the neighborhood. It was a real treat to see the band marching down my street. I took pictures.

Okay, back to the book.

After the inaugural parade there were comments on a Youtube video as well as other negative feedback regarding their performance. The dance team was a little too spicy.

The point of the first chapter was to show where the school was in the late aughts. The next chapter goes back in time to the beginning, where academics were key and excellence was something to be achieved.

I have a whole post of her husband Dr. Peter Murray.

According to her New York Times obituary from March 17, 1982:

Mrs. Murray was a mezzo-soprano and a graduate of the Juilliard School. She composed religious music and was a member of the executive committee of the Hymn Society of America.

Noted DC photographer Robert S. Scurlock took her portrait.

This really is a post about nothing in particular. I was just looking to see if she was located on Find A Grave…. she was not. And I found images of her and decided to share.

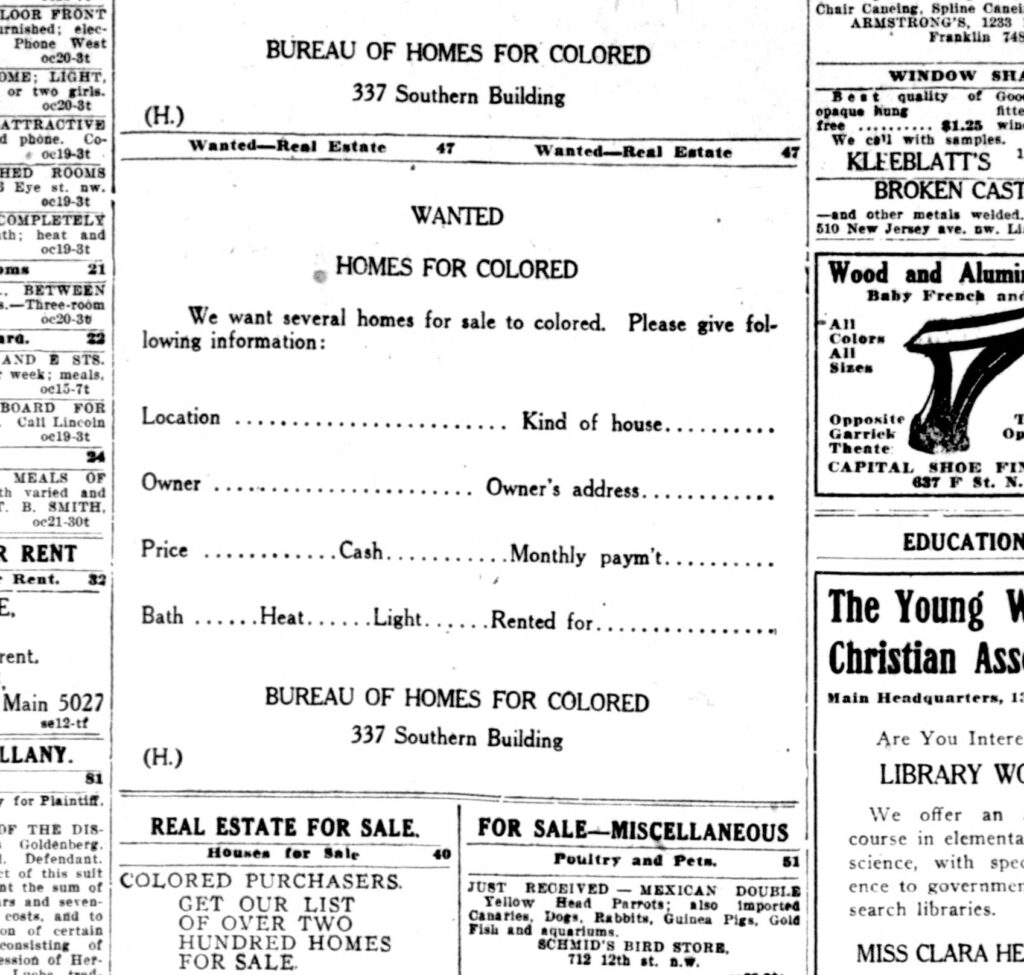

While researching another topic I noticed in the newspapers around 1920 this odd thing.

Then I asked, what is this Bureau of Homes for Colored? Was it some agency to help African Americans buy homes in 1920?

Well beyond a few ads, I came up with bupkis searching Google. So I went back to Chronicling America and searched for 337 Southern Building. A lot of businesses operated out of that office building.

Looking off to the side I noticed W. H. Saunders’ ad for real estate loans. The ad read “REAL ESTATE LOAN MONEY TO LOAN- $250 to $600,000 in D.C. real estate. Several trust funds. All transactions conducted with economical consideration for borrowers.” Doing these histories I notice a lot of people used lenders other than banks to borrow money to purchase a home.

Back to 337 Southern Building, Bradford and Company Inc, out of that address, had an ad in the April 29, 1921 Washington Times to sell a home to Black home buyers in NE DC for $2,500 with $250 down for $30 a month. Same page a home in LeDroit Park for $2,000, with $200 cash down at $20 a month. Bradford and Co. also advertised homes to the general public as well.

It appears the Bureau of Homes for Colored was just an advertising scheme and not a real program for African American buyers.

This year for Black History Month we’ll review chapter by chapter Alison Stewart’s First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School. This is more Truxton Circle related then this blog’s previous annual looks at Shaw resident and founder of Negro History Week (later Black history month) Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s Mis-Education of the Negro. As Dunbar High School is located in Truxton Circle currently taking up all of Square 554.

The Forward was written by author and political commentator Melissa Harris-Perry. She sets her part of the story in 2006/2007 during the Mayor Fenty years and mentions education reform. She then gives a wide sweep of the period the book covers which is about 100+ years where it goes from seeking excellence to mired in underachievement.

In the Introduction the author starts in 2003 with a plan to visit the school. When speaking to a local about the school the person gives mild praise to the basketball team. She entered and walked around with no one questioning her presence there. It was a far cry from the place her parents had described. She makes some useful points going forward reading the book about what we (as I too am African American) have called ourselves through time and that the author uses those terms. Another thing she wants readers to keep in mind are the school’s name changes. First it is the Preparatory High School for Colored Youth, then M Street High School and finally Dunbar.

In the introduction is a great point I will quote:

The story of Dunbar shows what can happen in spite of huge legal, societal, and professional hurdles. It shows what is possible when a group of people focus and band together to make something better. Dunbar shows what happens when a stable middle class exists.

Th Prologue is a snapshot from Obama’s inauguration January 20, 2009. A couple, Dunbar alumni who were teens in the 1940s were watching the inauguration on TV. They were inspired and hopeful with the start of the first Black president but were scandalized by the performance of Dunbar High School marching band.

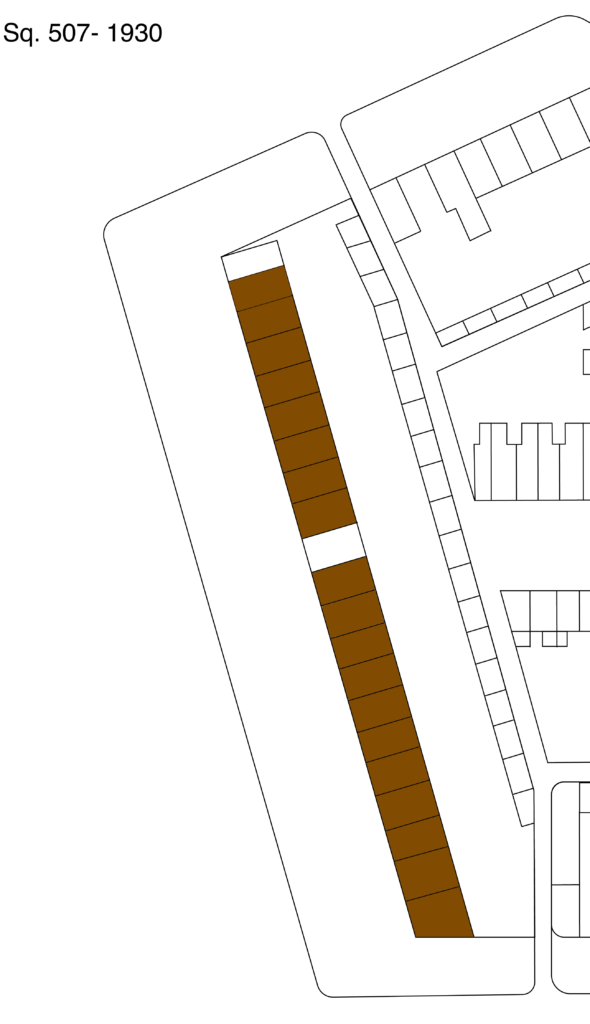

So I noticed a difference between the 1920 census and the 1930 census. In 1920 the odd numbered side of the 1700 block of New Jersey Ave NW was 100% white. In the 1930 census it was 100% black, as part of the trend happening in Truxton Circle changing the neighborhood from a relatively mixed neighborhood into one that was majority African American.

I had all sorts of theories, but never gave it much thought because there were other histories in the neighborhood to pursue.

Now that I am finally getting around to taking a closer look, I see a similarity to the 1950s sell off of the Washington Sanitary Improvement Company rental houses. Those houses were the last hold out where white residents lived and when they went up for sale those renters moved on. It also appears, and the problem relates to the DC Recorder of Deeds and when their records start, that there was single lender who made it possible for African American home buyers to buy.

Searching the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America for DC related post for one NJ Av address revealed the name of M. Harvey Chiswell as the seller. Searching for M. Harvey Chiswell on the LC’s site was disappointing. Let’s blame crappy OCR.

So I looked up in Ancestry who was M. Harvey Chiswell (1889-1952). Well apparently that “M” is for Mary. In the city directory around for her and she was a bookkeeper. In the 1940 census she was listed as a secretary and treasurer for an insurance company. I see how she could be in the position to facilitate loans and real estate sales.

Around July 1920 M. Harvey Chiswell purchased 1707-1715 New Jersey NW (lots 14-17) from Charles W. and Amy S. Richardson; 1717-1721 New Jersey Ave NW (lots 18-20) from Ella S. Du Bois; 1725-1731 New Jersey Ave NW (lots 22-25); 1733-1741 New Jersey Av NW (lots 26-30) from Mason N. and Ada F. Richardson, bringing that whole section of NJ Ave under one name, hers.

There was an announcement in the August 28, 1920 Evening Star to repair 1701-1741 New Jersey Ave NW by H. A. Kite.

1701 NJ Ave NW (Sq. 507 lot 10) was sold to Grace L. Jackson around September 1920 based on a deed of trust between her, W. Wallace Chiswell, H.A. Kite for $4,100 at 6%, secured by M. Harvey Chiswell.

1703 NJ Ave NW (Sq. 507 lot 11) was sold to Amelia Green by M. Harvey Chiswell around December 1920.

1707 NJ Ave NW (Sq. 507, lot 13) sold to Susie J.R. Johnson by M. Chiswell around October 1920.

1709 NJ Ave NW (Sq. 507, lot 14) sold to Julia G. Holland by M. Harvey Chiswell around September 1920. She also had a loan/ deed of trust between her W. Wallace Chiswell, H.A. Kite for $2,800 at 6%, secured by M. Harvey Chiswell.

1711 NJ Ave NW (Sq. 507, lot 15) sold to Maria Jones by M. Harvey Chiswell around October 1920.

1713 NJ Ave NW (Sq. 507, lot 16) sold to Frank E, Smith by M. Harvey Chiswell around October 1920.

1715 NJ Ave NW (Sq. 507, lot 17) sold to Fred H.. Seeney et. ux. Hester based on a deed of trust between the Seeneys, W. Wallace Chiswell, H.A. Kite for $2,800 at 6%, secured by M. Harvey Chiswell.

1717 NJ Ave NW (Sq 507, lot 18) sold to Mayo J. Scott et. ux. Sarah by M. Harvey Chiswell around October 1920.

1719 NJ Ave NW (Sq. 507, lot 19) sold to William H, Randall et. ux. Katie by M. Harvey Chiswell around October 1920.

1721 NJ Ave NW (Sq. 507, lot 20) according to a June 1926 release from a loan with W. Wallace Chiswell, H.A. Kite, Mary L. Tancil purchased the property September 25, 1920.

1725 NJ Ave NW (Sq. 507, lot 22) sold to George B. and Alice Oliver by M. Harvey Chiswell around October 1920.

1727 NJ Ave NW (Sq 507, lot 23) based on a February 1924 release from a loan with W. Wallace Chiswell, H.A. Kite, Addie E. Webb purchased the property February 15, 1921.

1729 NJ Ave NW (Sq. 507, lot 24) sold from M. Harvey Chiswell to Ida M. Smith then to Arthur B. Wall around February 1921.

1731 NJ Ave NW (Sq. 507, lot 25) sold to Salvadora E. Smith by M. Harvey Chiswell around October 1920.

1733 NJ Ave NW (Sq. 507, lot 26) based on a July 1926 release from a loan with W. Wallace Chiswell, Harry A. Kite, James A. and Coralie Whitehead purchased the property November 1, 1920.

1735 NJ Ave NW (Sq. 507, lot 27) based on a January 1925 release from a loan with W. Wallace Chiswell, Harry A. Kite, Mary S. and Milton C. Keasley purchased the property October 20, 1920.

1737? NJ Ave NW (Sq 507, lot 28) sold to James L. and Mary C. Johnson around September 1920, based on a deed of trust between the Johnsons, W. Wallace Chiswell, H.A. Kite for $2,900 at 6%, secured by M. Harvey Chiswell.

1739 NJ Ave NW (Sq. 507, lot 29) based on an October 1923 release from a loan with W. Wallace Chiswell, Harry A. Kite, John Holmes Jr. purchased the property September 23, 1920.

I have not reviewed all the houses along NJ Avenue to determine if the buyers mentioned above are the 1930s African American home owners. I do see some familiar names.

I’m continuing down the row of the odd 1700 block of New Jersey Ave NW in Washington, DC.

Why? Because I had a question. And with a few of these type histories, I figured out the answer. But just to confirm if it is true or not, I’ll keep going until I hit the end.

So let’s start with our 1920s White family renting 1707 NJ Ave NW the Troianos. They were there prior to the 1920 census. Joseph Troiano was the 38 year old head of the family at 1707 NJ in 1910. He was a self-employed tile setter from Italy. His wife Wilhelmina (Willie, nee Hurdle) (1881-1932) was a DC native and mother to their children Paul (1901-1904); Viola/Violet (1902-1993); Paul Alfred (1905-1930); Joseph Attilio (1907-1922); and Richard L. (1916-1976). The family also lived with two Italian boarders in 1910.

The father Joseph died in 1917 (1869-1917), so when the 1920 census rolled around Wilhelmina was a 38 year old widow with 4 children. She had one roomer, a 56 year old widowed chamber maid. The roomer and 17 year old daughter Viola were the only ones in the house recorded as to having a job in 1920. Willie’s sons were 14, 12 and 3 and unemployed.

Obviously by 1930 people moved on, to rent 522 7th St NE. Wilhelmina was still the head. She lived there with 13 year old son Richard, daughter Viola, son-in-law Lawrence Zacarin (1900-1989), and two lodgers (one is related somehow). Viola was working as a clerk for the Red Cross and her husband was a marble cutter. Three of Mrs. W. Troiano’s sons had already died by the end of 1930 and she would pass in 1932. Since Viola and Lawrence were still on 7th St in 1940, I assume they raised Richard after their mother’s death.

The earliest land document I could find from the DC Recorder of Deeds is a 1926 loan document for Susie J.R. Johnson with the Washington Loan and Trust Company. She took out a number of loans with trustees and companies including the Perpetual Building Association and the Home Owners Loan Corporation. In 1931 she lost the home to foreclosure but managed to get it back the next year, only to lose it again in 1933.

So she managed to stick around for the 1930 census. During that census she was listed as a 44 year old widow and public school teacher. She lived at 1707 NJ Ave Av with her 17 y.o. daughter Clytie/Clutie G., and 43 y.olds Mr. and Mrs. Oliver and Johnie M. Petway.

There’s some confusion with the 1940 census. It has the Sabbs family at 1707 and Amelia Green at 1705. So I will assume the residents of 1709 are the residents of 1707. That would be a renter, Thomas Mitchell who worked for the post office, he lived with his wife Sallie and sister Mattie.

Then what of Mrs. Johnson? When it comes to women with common names, I typically don’t try too hard. The Ancestry algorithm seems to place her in Tallahassee, FL, ironing for a college laundry. I found her daughter, then a patient at the Glen Dale Sanitarium. They were reunited in the 1950 census, on the 700 block of 4th St. Susie was no longer working. Clytie had married a radio repairman Samuel Ruffin and they had a son Samuel Jr.