The Washington Sanitary Improvement Company (WSIC) was a late 19th century charitable capitalism experiment that ended in the 1950s. This blog started looking at the homes that were supposed to be sold to African American home buyers, after decades of mainly renting to white tenants.

Looking at WSIC properties they tend to have a pattern where the properties were sold to a three business partners, Nathaniel J. Taube, Nathan Levin and James B. Evans as the Colonial Investment Co. for $3 million dollars. Those partners sold to African American buyers. There was usually a foreclosure. Then the property wound up in the hands of George Basiliko and or the DC Redevelopment Land Agency (RLA). Then there were the odd lucky ones who managed to avoid that fate.

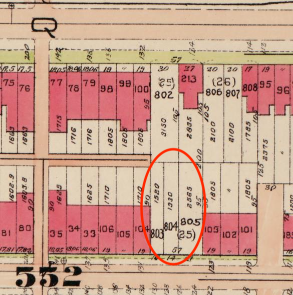

Let’s see what happens with 1549 3rd St NW:

- January 1951 Evans, Levin and Taube sold one-half of 1549 3rd St NW to Robert and Rosalie R. Moses.

- Jan 1951 Mr. & Mrs. Moses borrowed $3,900 from Colonial Investment Co. favorite trustees Abraham H. Levin and Robert G. Weightman.

- January 1951 Evans, Levin, and Taube sold the other half of 1549 3rd St NW to Jimmie and Lucille J. Nelson.

- Jan 1951 the Nelson borrowed $3,900 from trustees Abraham H. Levin and Robert G. Weightman.

- November 1952 the Nelsons transferred their half to Edith E. Matthews who transferred it to Ms. Lucille J. Davis.

- November 1961 Ms. Davis transferred her half to Ms. Frances R. Atwood who then transferred it to Jimmie and Lucille J. Nelson.

- December 1961 the Nelsons were released from their mortgage.

- March 1962 Mr. & Mrs. Moses were released from their mortgage.

I will end it here because the documents get a little too recent for comfort. A 1997 document mentions that Lucille J. Nelson and Lucille J. Davis are one in the same.

This was a good story as there were no foreclosures and the properties were owned free and clear by the original buyers.

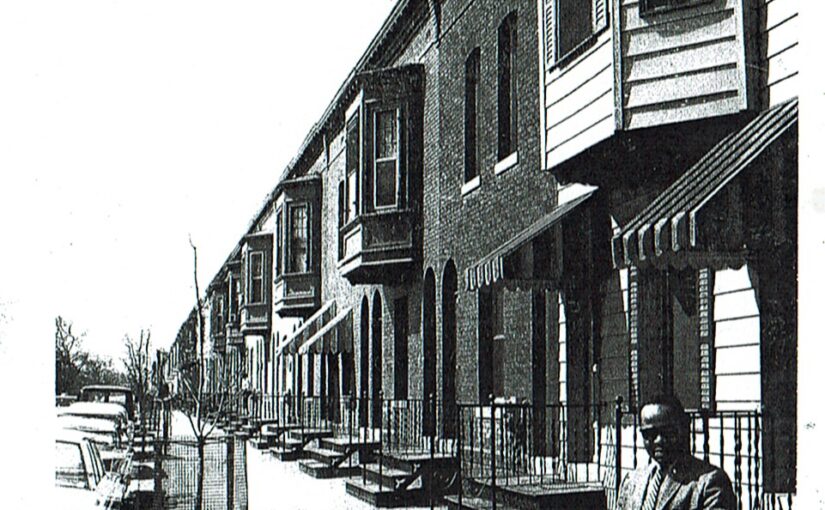

47 Bates Street NW

47 Bates Street NW