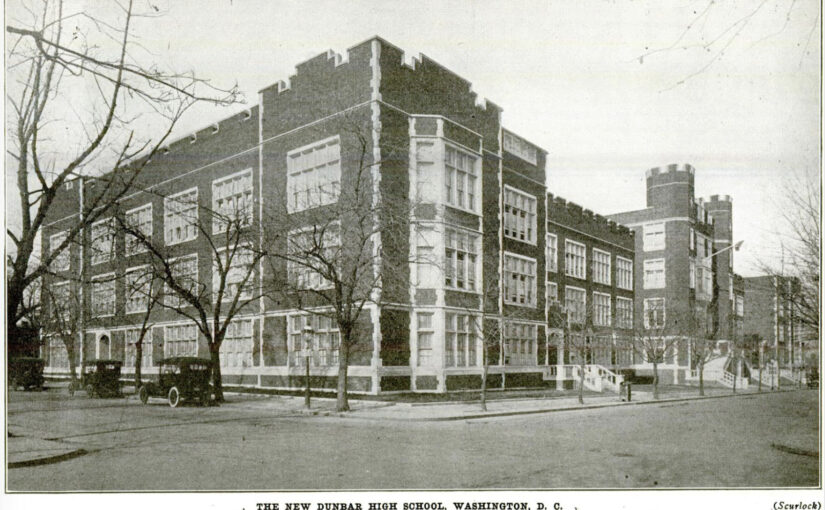

This year for Black History Month we’ll review chapter by chapter Alison Stewart’s First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School. This is more Truxton Circle related then this blog’s previous annual looks at Shaw resident and founder of Negro History Week (later Black history month) Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s Mis-Education of the Negro. As Dunbar High School is located in Truxton Circle currently taking up all of Square 554.

We’ve finally made it to the last chapter of the book and from the description the students and staff are still in the 1977 Dunbar building. It’s still hovering around the 2010-2011 academic year. The new building was in the process of being built, there was hope for the future of Dunbar.

There are three views of the school. The first takes place in Matthew Stuart’s English class. The second with Dunbar’s football team on Cardozo’s field. The third is back at Dunbar, in the basement.

It’s the start of the class in Mr. Stuart’s room and students are making their way in. Despite a rule against cell phones, one student came in speaking loudly on his. We’re also told less than half of the students enrolled in his class were present. A picture is painted of what Dunbar’s academics are like. Left unsaid is that they are a far cry from Dunbar’s beginnings.

Next, because of the construction for Dunbar’s new field and the change of layout of the school, the football team was at another school’s playing field. Coach Jerron Joe was a former Dunbar student (2004) and knew of other Dunbar alumni who moved on to the NFL. But Coach Joe did more than coach, he was also a mentor.

The last has us in the basement for girl’s track. This time with Coach Marvin Parker, and like Coach Joe, he’s a mentor to the girls, some of whom live under difficult circumstances. He wanted to break the cycle of poverty for girls, which at the time meant babies having babies. We’re told of a success story, Angela Bonham, who transferred to Dunbar and then excelled on the track and got a 4 year scholarship to GWU. Later we’re also told how Dunbar was essentially ignoring Title IX in favor of football, and Parker was an advocate for getting money for girl’s sports.

Dunbar may never be the academic powerhouse for Black education as it once was. But it is well known for it’s football team. Maybe it’s next chapter will be with athletics over academics. That’s fair. When I was looking at predominately Black private schools in the DC area, I stumbled upon a football schedule where a school I never heard of and couldn’t find was playing against DeMatha. What little I could find seemed to say the whole purpose of the school was for boys to play football. There are parents who value a school based on the school’s athletics. As a parent myself, I’m not going to fault another parent for their values, even if they strongly differ from mine. During the Covid shutdowns, there were Black parents who were very concerned about their sons’ high school sports careers. I found no fault with them.

When I was at the hair dressers getting my hair did, someone mentioned Dunbar. My first thought was for their dismal academic record. However, the barbers and the hairdressers spoke glowingly and lovingly about their football team. And again, I found no fault in them.

Let me conclude and get back to the book. This is a good history of Dunbar. It is not 100% about Dunbar. The author provides a lot of background information, necessary to understand and appreciate the parts that are about the school. I would highly recommend it to anyone who wants to learn about the great history of the school beyond a Wikipedia entry.