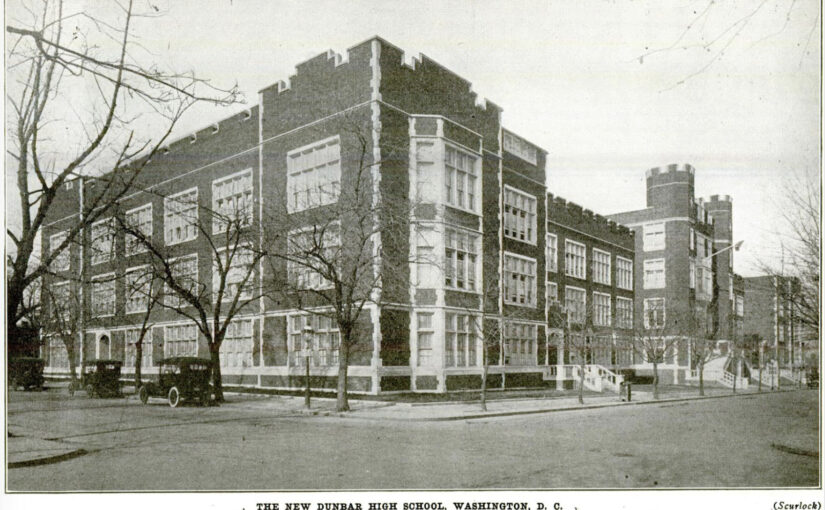

This year for Black History Month we’ll review chapter by chapter Alison Stewart’s First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School. This is more Truxton Circle related then this blog’s previous annual looks at Shaw resident and founder of Negro History Week (later Black history month) Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s Mis-Education of the Negro. As Dunbar High School is located in Truxton Circle currently taking up all of Square 554.

Most are familiar with Brown v. Board of Education. It is the US Supreme Court case cited and credited with desegregating American schools. What most don’t realize (because history seems to be a drive by affair where you briefly are told of a topic and then immediately run off to the next in the chronology) that Brown v. Board was made of 5 cases, a DC case being one of them. That DC case was Bolling v. Sharpe.

The note that a M St/Dunbar graduate, Charles Houston, was on the legal team seems unimportant. What the chapter does is give a sense of what public education was like for African American students in the 1950s. The previous chapters gave it for the 1940s and earlier. Both Dunbar and Armstrong were overcrowded in 1948, as well as the other Black high schools in the city.

May 17, 1954 the US Supreme Court made their decision on Brown v. Board and that year the District began a slow roll to desegregate starting at the elementary level. Of course, there was fighting. At least in the book, adults in positions of influence fighting about how the desegregation was going and planned.

I’m going to detour from the book to make a note. In the neighborhood had a smattering of white families in the 1950 census and by 1960, they’re gone. Doing the WSIC 1950 sell off series, I know why. It wasn’t because of school desegregation that had the families moving out. It was that those households were renters and their landlord WSIC decided to sell, specifically to Black buyers. Just looking at the census demographics and knowing about desegregation, it’s no great leap to assume that the change was due to the schools. Okay, back to the book.

“By 1957, Superintendent Hobart Corning declared, “Desegregation id complete.” But he then added this: “Desegregation is the moving about of people and things, Integration is a much longer process depending the creation of a community.”” So what does this mean for Dunbar, a school dedicated to Black academic excellence? Well it was the beginning of the end of that tradition and that culture.

Those fighting hard for desegregation weren’t thinking about Dunbar and what would come of its teachers and prospective students. Dunbar was on its way to becoming just a neighborhood school.