Shaw School Urban Renewal- Elementary Schools Map 1968

I believe I’ve posted this before. Not sure. These are the elementary schools of Shaw.

Slater and Langston seem to be joint schools.

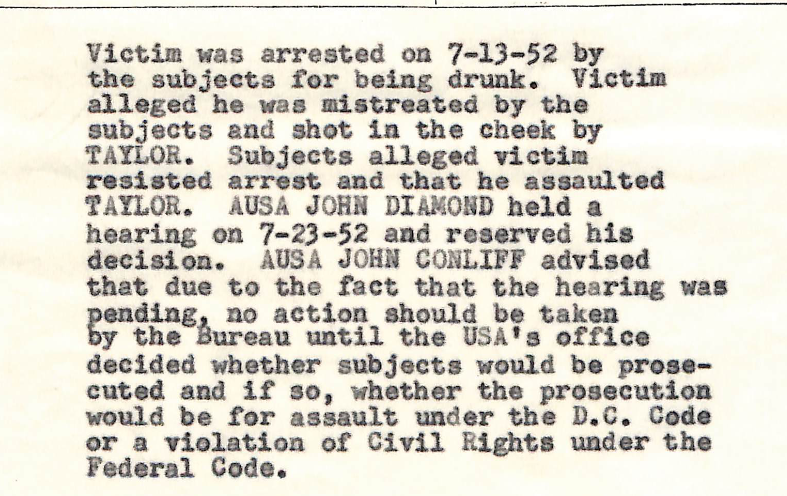

It happened on the 600 block of Rhode Island in 1952, part 6 of many

This is the second look at 144-16-95 [Frank Ray, Melvin Clements; Loran Lovan Taylor, Roland L. Gay – Victims] for information about an incident that happened around the 600 block of Rhode Island Avenue in 1952.

I’d been looking at the interviews fresh from the scene, however, I’m going to move to the final report that has all the interviews typed up. Reading cursive handwriting is too taxing.

So I’ll start with Mrs. Frances Smith who lived at 1707 Marion Ct/ Glicks Alley… which sort of no longer exists. She mention’s “Daddy Grace’s fence” this is the rear of the UHOP on the 1700 block of 7th St NW. Her words: Continue reading It happened on the 600 block of Rhode Island in 1952, part 6 of many

So I’ll start with Mrs. Frances Smith who lived at 1707 Marion Ct/ Glicks Alley… which sort of no longer exists. She mention’s “Daddy Grace’s fence” this is the rear of the UHOP on the 1700 block of 7th St NW. Her words: Continue reading It happened on the 600 block of Rhode Island in 1952, part 6 of many

It happened on the 600 block of Rhode Island in 1952, part 5 of many

This is the second look at 144-16-95 [Frank Ray, Melvin Clements; Loran Lovan Taylor, Roland L. Gay – Victims] for information about an incident that happened around the 600 block of Rhode Island Avenue in 1952.

The next statement comes from Frank E. Pinckney of 604 R St NW. The image is from a statement that someone wrote in cursive. The statement below that is from a report that compiled all of the witness statements. The two are slightly different.

From pp.94-96 of FBI 44-WFO-145, pp. 112-114 of DOJ 144-16-95:

“On Sunday, July 13, 1952, at about 6:30 p.m. I was sitting on the front steps of my residence at 604 R Street, N. W. There was no one else home at the time. My attention was attracted to the north side of R Street by loud talking and shouting. I looked up and at the west end of the hedge or the south side of the park I observed two white police officers with a colored prisoner. The officers were surrounded by about fifteen or twenty people. The people were shouting and hollering at the police officers and I thought that a riot was about to start as the people were crowding in on the officers and I didn’t know what might happen. I recall there were about six or eight cars parked on the north side of R Street.

I did not see any motorcycle parked. There were no cars parked on the south side of R Street, N. W. There were a few cars moving along R Street and some of them stopped and made the crowd larger.

The police officers each had a hold of an arm of the man and the man was between them. Because of the crowd and the cars my view was somewhat obstructed. The man was not walking but was being dragged along by the officers with his feet scraping along the ground. The man was pulling and twisting around and kicking out with his feet at the officers. They appeared to be having considerable trouble making their way along the sidewalk with the man. The police officers did not hit the man up to this time and were very busy trying to drag him along.

I do not know if the crowd touched the officers as I could

not see clearly because of the cars but the crowd was shouting abuse at the officers.

The officers continued struggling along with the man until they got just opposite my house between the second and third tree on the north side of R Street. At this point the man slumped down on the sidewalk. The police officers tried to get the man to stand up. The man was twisting and rolling around on the ground and kicking at the officers. The officers were struggling with him trying to get him to his feet, but could not get the man up. Because of the crowd and cars I could not tell whether any of the man’s kicks touched the officers, however, they were very close to the man and were wrestling with him and were rolling around on the sidewalk with him. Just at this point the man appeared to be getting out of

control entirely. One of the police officers, I didn’t know which one, then grabbed his night stick and struck at the man. I could not see where the blows struck the man but I could hear the man shouting “Don’t hit me anymore, don’t hit me anymore.” I estimate that the police officer struck only about three blows at the man. The other police officer did not strike at the man at all, he was engaged in trying to hold on to the man.

At this point my phone rang and I went into the house. I talked briefly on the phone to my brother, WARREN B. PICKNEY, of 428 Galt Street, N.E. I did not mention to him what was going on outside. While talking on the phone I heard one shot. I continued talking for a brief period and then when finished I came back out on my front steps. Just as I got outside on my steps again the patrol wagon got on the scene. There were then four officers present and a large crowd of 100 or more had gathered and people and cars were arriving from every direction. Because of the crowd I could not see the man. I continued to watch until the ambulance came and took the man away.

I would like to say that when I first saw the man he did not appear to have any blood on him or to be injured in any way. I could not see the man as he was being struck by the police officer. When the man was put in the ambulance I could see blood on his head. I could not see the man well enough at any time to tell if he had anything in his hands.

I would like to add that just before my phone rang one of the two officers ran to the call box at 6th and R Streets, N. W. I would not be able to identify either officer or the man if I were to see them again.

I did not notice if either officer had any blood or marks on, Him.

This statement was read to me as I forgot my glasses. It is true.

It happened on the 600 block of Rhode Island in 1952, part 4 of many

This is the second look at 144-16-95 [Frank Ray, Melvin Clements; Loran Lovan Taylor, Roland L. Gay – Victims] for information about an incident that happened around the 600 block of Rhode Island Avenue in 1952.

The next statement comes from Annie Gardner of 614 R St NW. I will do my best transcription.

“saw situation when officer shot man said he was lying on sidewalk when I first saw them they were in front of the lamppost dragging him along beating one went for the patrol wagon and one continued to beat while he was lying on the groung [sic] helpless. The officer fired three shots.”

It happened on the 600 block of Rhode Island in 1952, part 3 of many

This is the second look at 144-16-95 [Frank Ray, Melvin Clements; Loran Lovan Taylor, Roland L. Gay – Victims] for information about an incident that happened around the 600 block of Rhode Island Avenue in 1952. Last we had Mrs. Mildred Johnson of 516 R St NW, statement. This post has her husband, Mr. Travanyon Johnson . He doesn’t add much.

STATEMENT

TRAVANYON JOHNSON

516 R Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C.

I saw the same thing my wife saw, and the man did not

have a knife. If he had one he couldn’t get to it anyway. If the officer had been cut, you could have seen the blood on him, and I saw no knife. The officers shirt was not torn. The man had no power of any kind to do anything to the officers.

Travanyon Johnson

***

I don’t know why the statement about the knife was removed. I know that the prospect of Zeke having a knife and cutting one of the police officers comes up later in the file.

It happened on the 600 block of Rhode Island in 1952, part 2 of many

This is the second look at 144-16-95 [Frank Ray, Melvin Clements; Loran Lovan Taylor, Roland L. Gay – Victims] for information about an incident that happened around the 600 block of Rhode Island Avenue.

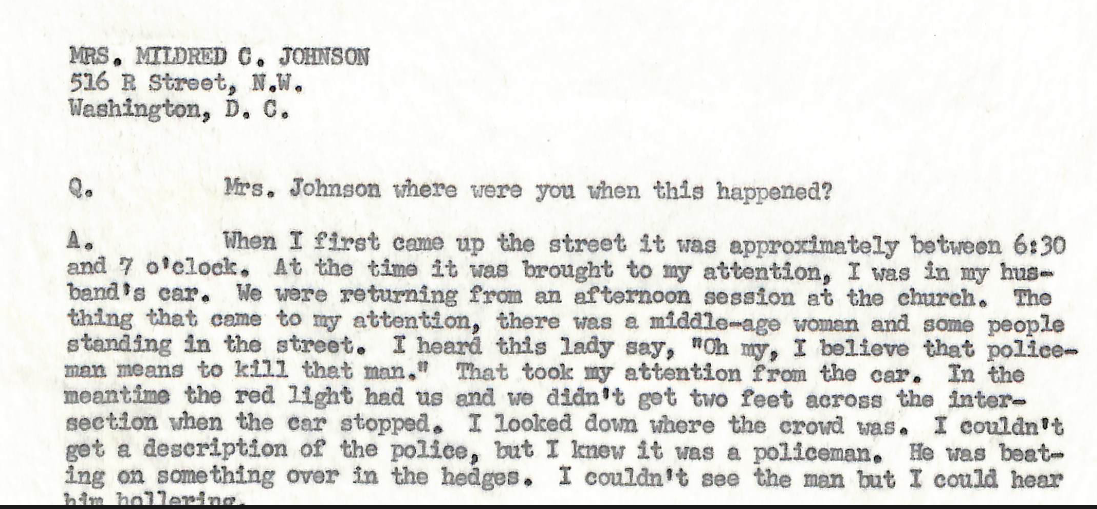

Today we will look at a statement from Mrs. Mildred C. Johnson who lived at 516 R St NW.

STATEMENT

MRS. MILDRED C. JOHNSON

516 R Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C.

Q.

Mrs. Johnson where were you when this happened?

A.

When I first came up the street it was approximately between 6:30

and 7 o’clock. At the time it was brought to my attention, I was in my husband’s car. We were returning from an afternoon session at the church. The thing that came to my attention, there was a middle-age woman and some people standing in the street. I heard this lady say, “Oh my, I believe that policeman means to kill that man.” That took my attention from the car. In the meantime the red light had us and we didn’t get two feet across the intersection when the car stopped. I looked down where the crowd was. I couldn’t

get a description of the police, but I knew it was a policeman. He was beating on something over in the hedges. I couldn’t see the man but I could hear him hollering.

Q.

How many times did this police officer strike this man?

A.

I don’t know because this was going on before my attention was

called to it. He must have struck him 3 or 4 times when I noticed it. At this time the billie broke in half. At that time it seems the man might have tried to get to his feet. No sooner than the billie was broken the policeman went in his holster and went bang, bang, bang.

It happened on the 600 block of Rhode Island in 1952, part 1 of many

There is a huge file from the Department of Justice about an incident that occurred around the 600 block of Rhode Island Avenue NW in the early 1950s.

The file we’ll be looking at is 144-16-95 [Frank Ray, Melvin Clements; Loran Lovan Taylor, Roland L. Gay – Victims] and you can look at this 240 page thing on the National Archives Catalog.

The investigation is mainly about a guy named Ezekiel “Zeke” Seigler, whose civil rights may have been violated when he was beaten by MPD. I’m going to spoil the ending. Nothing happens.

Seigler was an alcoholic who didn’t remember the beating. He made for a crap witness so therefore, nothing happened. But that’s not the interesting part. The interesting part is all the stuff brought forward from the investigation.

Despite it being a DOJ investigation, the FBI did the investigating and wrote up the reports. Zeke was arrested for being a drunk and was reportedly shot by Officer Taylor in the face.

Yes, I’m going to drag this one document through for a couple of months.