The Washington Sanitary Improvement Company (WSIC) was a late 19th century charitable capitalism experiment that ended in the 1950s. This blog started looking at the homes that were supposed to be sold to African American home buyers, after decades of mainly renting to white tenants.

Looking at WSIC properties they tend to have a pattern where the properties were sold to a three business partners, Nathaniel J. Taube, Nathan Levin and James B. Evans as the Colonial Investment Co. for $3 million dollars. Those partners sold to African American buyers. There was usually a foreclosure. Then the property wound up in the hands of George Basiliko and or the DC Redevelopment Land Agency (RLA). Then there were the odd lucky ones who managed to avoid that fate.

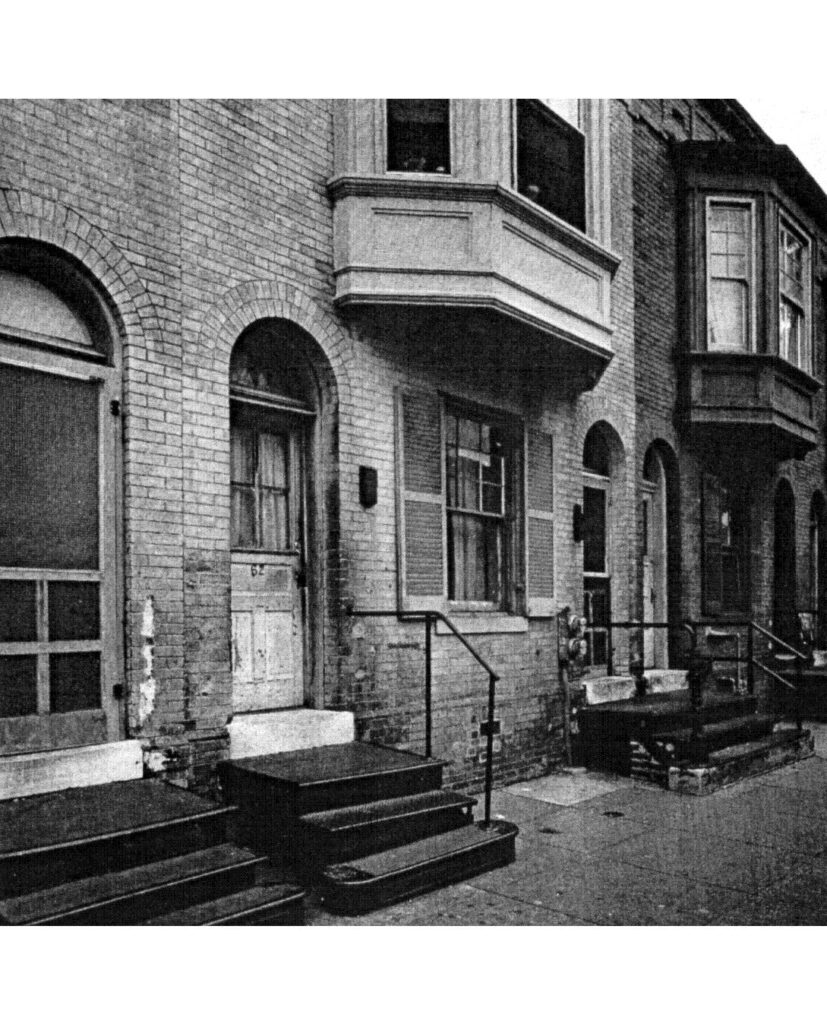

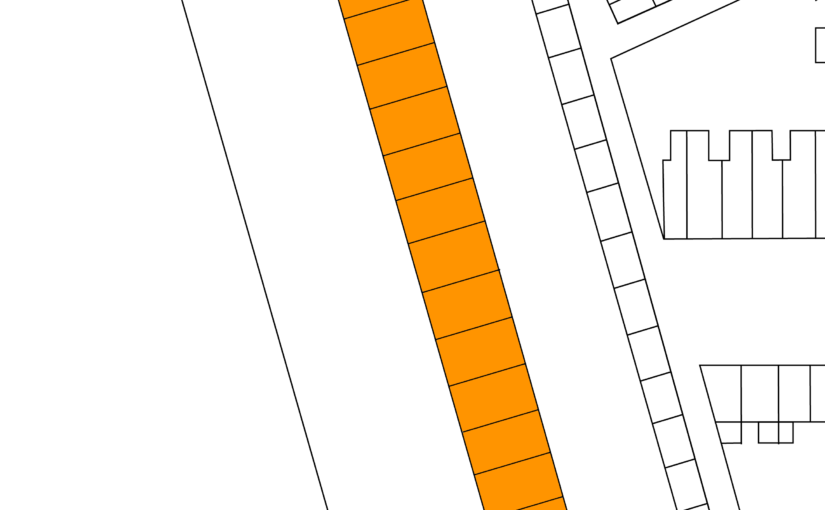

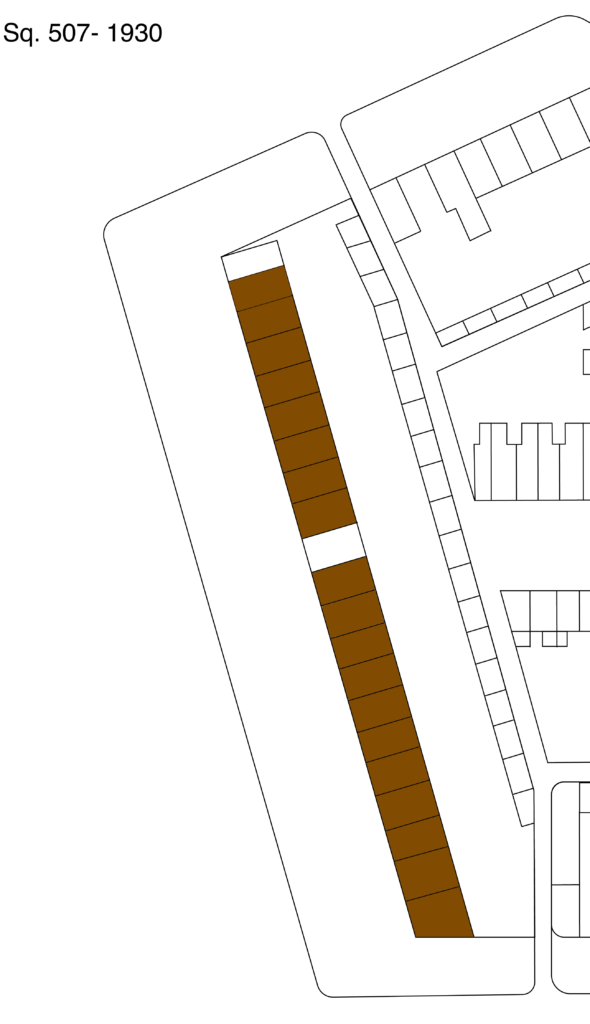

Let’s see what happens with 211 Bates St NW:

- December 1950 (recorded Jan 18, 1951) Evans, Levin and Taube sold one-half of 211 Bates NW to Malachi and his wife Vancie L. Payne.

- December 1950 (recorded Jan 18, 1951) the Paynes borrowed $2,525 from Colonial Investment Co. favorite trustees Abraham H. Levin and Robert G. Weightman.

- January 1951 Evans, Levin, and Taube sold the other half of 211 Bates St NW to Ernest Bailey.

- Jan 1951 Bailey borrowed $2,525 from trustees Abraham H. Levin and Robert G. Weightman.

- March 1953, Ernest Bailey who was reportedly divorced and ex-wife Katherine Lea Bailey sold the property back to Evans, Levin and Taube. He was released from the mortgage in May.

- June 1953 Evans, Levin and Taube sold the resold half to Julius and Kathleen James.

- June 1953 the James borrowed $3,274.21 from Levin & Weightman.

- September 1955 the James lost their half to foreclosure and it returned to the ownership of Evans, Levin and Taube.

- June 1959 (document # 1959024641) Evans, Taube, new partner Harry A. Badt, Nathan Levin’s survivors, and their spouses sold 211 Bates, as part of a large property package, to Sophia and George Basiliko.

- May 1978 the Paynes sold their half to George Basiliko Inc.

- August 1978 the Basilikos sold the property in a larger package to the Bates Street Ventures Partnership….. not sure if that is anyway related to the Bates Street Associates (BSA).

There was a foreclosure and property was sold to George Basiliko. It managed to avoid getting sold to the DC Redevelopment Land Agency and the Bates Street Associates…. I think.